This Saturday, we held a memorial service and reception in honor of my mother, Gabrielle Stephens (née Stransky), who passed in her sleep early in the morning on July 18th, as the final act in a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease. My father, the most loyal companion anyone could have, cared for her at home for as long as he could, then remained by her side in assisted living until the very end. My sister and I had been traveling to visit them monthly, and I’m grateful that we had enough advance warning to spend her last two days together with her.

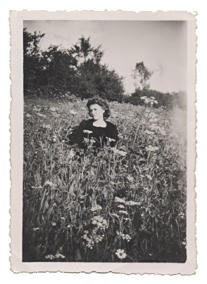

My Mom was born and raised in the small rural town of Bogros-Messeix, in the Auvergne region of central France, and I remember her as a generously happy person. She found joy in the world, and seemed to want more than anything to share it with us — which she managed to do the moment you saw her. She always had a smile to greet you with, and it was impossible to be or remain gloomy in her presence. Her laugh, that I know all who knew and loved her can still hear, and her delight in little things, were absolutely contagious.

Being gracious and hospitable was tremendously important to my Mom, and came to her naturally, as it did to our dear aunt, her sister Marie, and her restauranteur husband Raymond. Growing up alongside their daughters, Raphie and Zizi, we enjoyed the extraordinary circumstance of our families living near one another in West Los Angeles, and making a point of getting together often — a situation whose rare preciousness I can only now truly appreciate. Marie and Gaby took turns hosting Thanksgivings, Christmases, and Easters, bringing together not just our two families, but also longtime friends from the French community, who became a true part of that family. Those lively gatherings were full of a kind of warmth and gracious delight in one another’s company that I wish everyone would get to experience in some form in their lives. Those times seem far away now, but they will always be with us. And we are reminded to strive to carry on what these sisters and their husbands so skillfully and lovingly began.

Gaby’s parents had emigrated to France from Czechoslovakia, and I don’t know whether many French ever considered her and her family truly French, but to the adoring parents she effortlessly charmed at our elementary school, her credentials as a sophisticated, delightful Frenchwoman were beyond question. My Mom briefly taught a French language class in the library for some of the children. In going through things, I found we still have her extensive notebooks and handwritten flash cards from that project, where she jotted down phrases and translations and details of grammar that she must have had to research well beyond what she’d had the chance to learn in her short schooling. She did it all with great joy. And those lucky kids got to taste the world’s best homemade crêpes, too.

Though timid about some things, my Mom could have a surprising sense of adventure and willingness to try, or be talked into, new things. I remember one particular afternoon, spent with Dad’s family on Deer Creek reservoir in northern Utah. We somehow managed to get my Mom on a Jet Ski, without explaining that gripping the handles for dear life also squeezes the throttle full open. Fortunately, the time for her to leave us was not yet.

Mom arrived in the United States by boat in 1952 — sailing into New York Harbor on the Ile de France to join Marie and Raymond in Chicago. The three worked there as house servants for a time, before moving to Palm Springs, where she met and married her first husband. When his his postwar Army service as a chef to Allied officers took them to Paris, Mom enrolled in esthéticienne training.

On their return to the U.S., Mom put her new skills to use in a successful career at the Beverly Hills salon of Aida Grey. After they divorced, she opened her own salon, which as luck would have it led to being introduced to my Dad by one of her adoring clients. They met and married in 1968.

I’m the second of Mom and Dad’s three children. Veronique, the big sister we never had the chance to know, was born two months premature and never managed to take a breath. Dad is working on reuniting her remains with theirs.

I remember Mom’s occasional need to renew her status with the French consulate when I was a kid. When she decided to earn her U.S. citizenship, she studied hard for it. It must have been one of the bigger challenges my mother undertook. But she saw it through, and we were as proud to be there in support of her at the swearing-in ceremony in 1990 as she very clearly was to have achieved it, and to have formalized the affectionate ties she already felt toward her adopted country.

Mom worked hard for us, diligently and without ever slowing down or giving up. She toiled and sacrificed, so that we could live well. She kept an impeccable home. She made sure we got to go places. She had our friends over. (Nobody ever left our house hungry.) She took us to the park, to the beach. She and Dad took us to Disneyland, Knotts Berry Farm, and the Sequoias. My Mom braved a terrifyingly short 3-lane change on the 10 highway in L.A., to get me to Saturday science camp at Exposition Park. I know that part of the drive terrified her and she dreaded it. But she overcame that fear. For us. She made sure we had a full and happy childhood.

The joy my Mom experienced in life, and her glowingly positive attitude, somehow survived the difficult years she grew up in. Her family lived through some lean and fearful times that are hard for us to fully appreciate today.

Mom’s family were of modest means. Her father, brother Emil, and brother-in-law Leon worked in “La Mine” — deep underground, in the town’s coal mine. Their father proudly and stubbornly endured work in waist-deep water, for attending the wrong church. For part of Mom’s childhood, their town in France was under Nazi occupation. She told us stories of living life under the watchful eye of German soldiers — men who gassed people in churches, men whose belt buckles read, “God is with us”, leading her to wonder: “If God is with you, then who will help us?” She remembered darting furtively through their garden in winter to dig up buried cabbages in the snow and bring them back to the house, worrying all the while that she was being watched. She remembered her mom carrying grenades in her apron, to bury them in that same garden. They belonged to her brother Emil, who was part of the Maquis — the French resistance — and she was worried they hadn’t been well hidden. You can imagine the family’s constant concern that they would be found out.

The war wasn’t the only hardship the family endured. Their mother, Bozena, an educated midwife who delivered most of the town’s babies, passed on September 1st, 1947, when Gaby was only sixteen — leaving her and her siblings, Marie, Elise, and Emil, to care for their father and one another. Bozena suffered from a heart ailment that ended up being made worse by her treatment, and as a result she was taken from her family too soon.

My Mom had sweet memories of growing up in Bogros too. The hills and woods where they played. Her father fishing, sitting on a boulder in the middle of the Dordogne. (That, more than anywhere, must have been his “happy place”.) “Chercher champignons” — Hunting for wild mushrooms in the woods. Gathering water at the fountain with her dear lifelong friend Emma Pavlovsky. The sweet smell of tangerines her mother had hidden under the stairs (a rare treat then), which my Mom always said was how they knew Christmas was coming.

Mom remembered her sister Marie sneaking sweet treats from the sugar bowl now and then. Her brother Emil famously helped with dental and electrical chores. (When one of them had a loose baby tooth that needed tending to, he’d dutifully tie a string to it, tie the other end to a doorknob, and … you can imagine step 3. When Emil needed to check whether the electrical outlets were working, a sister’s well-placed finger would do the job just fine.)

My Mom surviving all of that and making her way to the United States, and eventually to Los Angeles where she met my Dad, was a big stroke of luck for all of us. We lived many years there, in a life we were lucky to have.

I remember where I was, coming up our old back steps to the kitchen from playing outside, when Mom told me she’d had a phone call from France, and learned that her father had died after a battle with cancer. She said she had known it before she received the call.

In 2004, we lost my Mom’s sister Marie, who was brutally taken from us all far too soon. We all felt the loss deeply; Mom most of all.

With my mother’s passing last week, their sister, Elise — who lives in an assisted living home in France, attended by her daughter Dany — is now the last of the Stransky children. The world will never again be as bright, when they all are gone.

Alzheimer’s takes a person from you piece by piece, with heart-rending cruelty. By the time my Mom passed, I was already well down the road to missing her tremendously. But I’ll be eternally grateful for the beautiful life she got to live, for all the love and care that she gave us so generously, and for my father’s steadfast devotion and the undying love that kept them together to the last.

“You’re my sweetheart, and I’ll love you forever,” he said at the very end. I can’t think of a more beautiful way to say such a difficult goodbye.