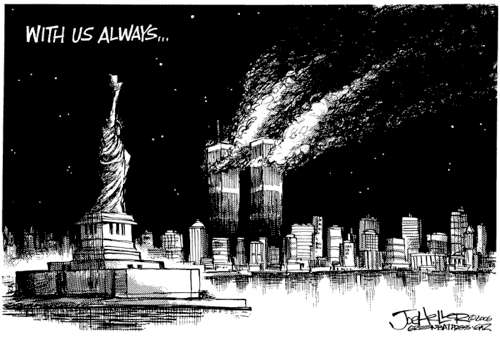

In past years, I’ve written about where I was on 9/11, posted quotes, written about songs, tweeted the names of victims, and recommended blog posts, articles, and videos. But on nearly every anniversary of the 9/11 al Qaeda attacks since I started blogging, the unifying issue on my mind has been nearly the same: To assess where we are and how we are faring some years after.

Reviewing what I’ve written in years past, I find that my answer to that question has changed very little, and the farther we get from that awful day the more that fact worries me, for despite having successfully thwarted at least 19 subsequent would-be attacks, I don’t think we’re faring very well as a culture, in crucial ways that for me raise serious questions about what our long-term future will hold.

I try not to let the gloom envelop me. In so many ways, I am an optimist in my heart of hearts. I have tremendous confidence in our culture and way of life, in our resilience and adaptability, and in all that we can achieve with our ingenuity and dedication and mutual goodwill. Yet it kills me to see that same culture mired in and hobbled by an unwarranted mentality of self-recrimination and self-doubt, and simultaneously unwilling to candidly examine and confront an ideological movement that is actively, deeply, vocally, immutably, and demonstratedly hostile to its foundational principles and continued existence.

What does it mean to live in a culture that is only just barely willing to stand up and fight for itself in the wake of a horrific act of war such as the 9/11 attacks? I would not have thought our present-day frame of mind possible to sustain after such an event, but the cultural and political divisions that predated 9/11 have proven far more resilient than I would ever have expected. We didn’t wake from our slumber of infighting to pursue, united and with doggedly committed determination, the defense and preservation our nation and way of life; rather, we retrenched and resumed fighting each other, our cultural fault lines painfully underscored in the process. As Michele Catalano wrote three years ago,

In so many ways, 9/11 ended up furthering any divisions we had instead of closing them. We chose up sides and backed away from each other as if we were our own enemies —- as if the enemies we had, those who steered planes into buildings, weren’t enough.

This realization, and the seeming impossibility of bridging the chasm, has been a knife in my heart ever since. It kills me. But I don’t see any way around it.

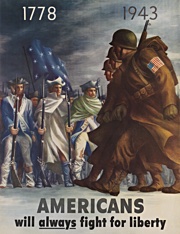

So many aspects of our cultural condition have caused me grief over the past ten years. I feel crestfallen that it is taking us as long as it has to rebuild at the World Trade Center site. I’ve felt deeply betrayed by a Hollywood that now routinely denigrates and vilifies the country whose values and achievements it once celebrated and defended, a Hollywood that I loved in my youth but have now all but written off and given up on. I have been deeply disappointed in a supposedly mainstream American press that seems to have seen it as its sworn duty to demoralize us and convince us of inevitable defeat and dishonor in the wars we’ve prosecuted, in a way that’s been shown to be transparently contingent on the political party of the President in the White House. I’m troubled that over the past three years, we’ve largely acted in ways that can only serve to embolden our enemies, while giving our friends and allies and those we should at least be lending moral support in their fight for freedom and against totalitarianism (c.f. Iran’s democracy activists, and other participants in the recent “Arab Spring” uprisings) scant reason to hope for the backing of a country that has for so long been thought of as a beacon of hope and the moral “leader of the free world”. It makes my heart sink that too many of our own citizens seem to believe that America is the problem in some form or other.

All of these cultural factors pain me and deeply trouble me, but on this 10th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks I’m willing to largely put them aside in the interest of getting just one, crucial point across regarding the single most dangerous problem we face: the inability or unwillingness to name, frankly discuss, and squarely face our ideological enemy. More than anything else, it is a commitment to reckoning with this circumstance that needs to cross the perhaps otherwise impassable ideological chasm that separates the American Right and Left.

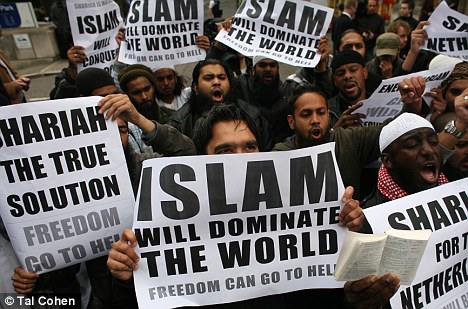

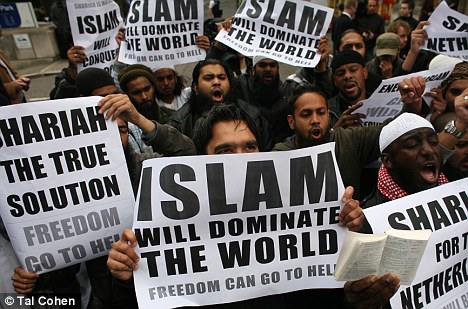

We can and will continue to differ with our countrymen regarding specific policy prescriptions, including matters of war. I could perhaps accept that, in a world where I felt we had all made a candid and fully informed assessment of the adversary we are up against. But there are still many among us who don’t seem to want to look Islamic Supremacism in the face, or even acknowledge its existence, either because the prospect is too frightening, or because the acknowledgment would violate long-practiced “PC” rules of cultural conduct that are so deeply ingrained in us, we fear we wouldn’t know how to function without blindly deferring to them. If I could make one plea to my fellow countrymen, Left, Right, and Center, it would be this: Please, please look with open eyes at what we are up against. Even if you must conclude that Islamic Supremacism is a fringe ideology with no real possibility of gaining dominance or causing substantial long-term harm to the free world (I truly wish I could believe it was so), do so with a full understanding and awareness of what the Jihadists intend for us, far-fetched or not, as detailed in their own words and actions: the return of a 7th century Caliphate that is fundamentally incompatible with and hostile to secular and pluralistic free societies, with all the attendant implications for women, homosexuals, infidels and religious and ethnic minorities. These Jihadists have told us their intentions time and time again, but we somehow refuse to believe them.

We are so conditioned to reflexively genuflect to any and every other culture as a show of goodwill, that both our critical thinking faculties, and our courage to overcome fear of social reprisals and voice our honest concerns, seem to have become disengaged or defunct. If every culture and religion in this world was as benign in its intentions toward us as most are, this willful blindness wouldn’t be a big problem. We could all live together in happy harmony and the “coexistence” that so many understandably wish for. But the fact that most others have relatively benign intentions has disarmed us to the crucial few that do not. Our cultural defenses are down — way down — and even being caught off our guard ten years ago with horrific consequences doesn’t seem to have changed that sufficiently. Informing and educating ourselves about what we’re up against is crucial, for we cannot expect to remain both ignorant and free.

Is this state of denial (or leaning strongly toward diplomatic use of language, if you prefer) causing any real problems? It certainly seems to be. How else could a man like Nidal Malik Hasan remain in active service in the United States Army, after repeatedly making statements against the United States and in sympathy with our Jihadist enemies? There are compelling and deeply troubling indications that not only our armed forces, but our broader defense and law enforcement agencies are compromised in their ability and sworn duty to protect this country and its citizens by pressure to whitewash reality, sanitize the use of language that could be perceived as hurtful or offensive, and shrink from confronting reality. We are letting organizations such as CAIR — a front for the Muslim Brotherhood, whose charter calls for a “grand jihad in eliminating and destroying the Western civilization from within and ‘sabotaging’ their miserable house by their hands and the hands of the believers so that it is eliminated and God’s religion is made victorious over all other religions” — advise our FBI on how to combat violent Islamic radicalism.

Bill Whittle’s April 7, 2010 PJTV piece “The Censorship Agenda” revealed in worrisome detail the sanitizing of our foundational national security documents that has taken place since the original, bipartisan 9/11 Commission Report. (As Bill himself suggests, contrary to the provocative subtitle “Obama Bans ‘Islam’”, the culture of self-censorship and willful blindness that produced these results may very well be indicative of a long-extant problem that predates the Obama administration.)

Think about the implications of Bill’s findings: in stark contrast with the comparatively frank and sober assessment of the 9/11 Commission Report (whose use of key terms is tabulated in the leftmost column, below), the FBI’s 2008 Counterterrorism Analytical Lexicon (next column), our 2009 National Intelligence Strategy report (next column), and the Protecting the Force: Lessons from Fort Hood report on the shooting rampage by Nidal Malik Hasan (rightmost column), use the terms “Islam”, “Muslim”, and “Jihad” a total of zero times.

Zero.

The National Intelligence Strategy report doesn’t even reference “al Qaeda” or use the word “enemy” (employing, instead, the term “violent extremist”, a total of 29 times). The DoD’s Fort Hood report, amazingly, makes no reference whatsoever to “violent extremism”, “Islam”, “Muslim”, “Jihad”, or even to Hasan’s name.

Think about this. Disregard, for the moment, our popular culture and variously informed conversation among Joes like you and me. How is it possible that the very institutions we charge with our defense — whose analyses one would expect, of necessity, to be unflinchingly sober and frank — have become this willfully blind?

I can only shake my head in near-despair at the self-sabotaging ridiculousness of it. It might be funny if the consequences weren’t so dire for all of us. (Bill, however, has a more upbeat outlook than I do this year.)

Forget about applying the non-lethal (but awfully emotionally insensitive) tool of humor by mocking our enemies, which appears to be completely out of the question save for a few valiant out-of-the-mainstream efforts such as Shire Network News and Sands of Passion. In most cases, we can’t even bring ourselves to precisely and candidly refer to them. If our thinking and definitions are clear, there should be no reason not to do so, given all that is at stake.

This man has the right idea (emphasis mine):

There is nothing insulting to decent, good members of the Muslim religion when I say “Islamic extremist terrorist”, any more than it is insulting to the Italian-American community (when I was a prosecutor) to say the word “Mafia”. Or that it would be insulting to decent Germans to say the word “Nazi”.

One mistake to avoid is political correctness. You can’t fight crime, and you can’t deter terrorism, if you are hobbled by political correctness. I believe that Major [Nidal] Hasan is an example of that. There is no way that Major Hasan should have been a major in the United States Army, after several years of spewing forth hatred for the United States of America… I would consider Major Hasan’s attack on Fort Hood an Islamic extremist terrorist attack. I have a hard time understanding why the government doesn’t see it that way, since he was yelling “Allahu Akbar” when he started killing people. …

… We cannot use this as an opportunity to say, “let’s put this behind us”, because if we we do that, we will repeat the mistake that we made before September 11th, which is not evaluating correctly the scope and the danger of Islamic extremist terrorism. Notice I use those words and I use them often. I do because I have a simple belief: If you can’t face your enemy, you can’t defeat your enemy. If you can’t honestly describe your enemy, there are distortions in your policy decisions as a result of that.

Re-read that last part, and internalize the essential lesson: If we refuse the accurate use of words, we are sabotaging ourselves.

Since accusations of “Islamophobia”, etc. are now flung automatically against any who express concern about Islam’s militant political arm as exemplified by the likes of al Qaeda and Hamas, let me be as clear as it’s possible to be, knowing full well that “it is impossible to speak in such a way that one cannot be misunderstood” (or willfully misinterpreted): I really don’t want to spend my time writing and thinking about this stuff. I have no intrinsic need to gratify myself or feel superior by grinding ideological axes against either an external enemy culture or my own countrymen. I’d much rather invest my time and energy inventing, innovating, creating, raising my son, spending time with my wife, living and working and striving to do better among peers whose origins span the globe, but who share a necessary basic dedication to the essential principles of a free society. I would love nothing more than to be decisively proven wrong about all of this, and get back to my life. I think and write about this kind of stuff because, as far as I can tell, there is no avoiding it. The very culture that furnishes and protects my ability and yours to live our lives as we do and freely engage in such humanity-advancing work, is under attack by another that demands our submission to a suffocating, stifling, totalitarian ideology. If we cannot name, discuss, and confront that ideology, we might as well surrender to it.

My “endgame” — the long-term future I hope for — is not a perpetual state of war (who would wish for that?), but a true coexistence of stable peace and security that can only exist after the Islamic Supremacist threat has been acknowledged and somehow neutralized. That is to say, I seek a peace worth having. To whatever extent we can accomplish that without resorting to the use of force and violence, wonderful — you have me on your side. I want and hope for a future where I can freely live, work, and prosper alongside all others who share my commitment to upholding the essential principles of our free society, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, regardless of where on the globe they hail from, without any of us having to fear violence from totalitarian nutjobs. There is too much to do and achieve for us to waste our time, capabilities, and resources on war where we have a reasonable alternative. But to shrink from the last-resort necessity of war when it is upon us seems to me no less a betrayal of the society we rightly cherish, for if left undefended that society will crumble.

I speak “peace”, when peace is spoken.

Even when we are not in our worst moments of genuflecting self-censorship, our choice of terminology has been clumsy, muddled, and unhelpful from the start — and, make no mistake, these poor choices of terminology sink us. Case in point: A “War on Terror” is no more meaningful than a “War on Blitzkrieg”, or a “War on Kamikaze strikes. Terror is a tactic, not an identification of the ideology that motivates its perpetrators. The ideology we’re up against is is most accurately described as “Islamic Supremacism” — a militant, political branch of Islam that sees as its imperative the subjugation under strict Islamic law (Sharia) of all non-Muslims and any who wish to live in free and pluralistic societies. To attempt to broaden our response to al Qaeda’s brand of violent Islamic Supremacism into a “War on Terror” is to dilute our sense of purpose, and pretend against evidence that there are just as many terrorists motivated by various other ideologies who pose an imminent threat. This awkwardly vague and clumsy choice of words was, I think, both an attempt to avoid any reference to or indictment of any sect of “Islam”, and a well-intentioned overture of comradeship to other nations who had suffered terrorist scourges of other origins, but in the end I believe it’s been an ill-advised one. Since we’re not supposed to draw any connection between acts of terrorism and even a small, extreme, ostensibly non-representative minority fringe of Islam, we try to make do with the unhelpfully vague “War on Terror”, and it’s a wonder if we don’t forget what, in fact, we are fighting against.

I’m out of words, but I hope I’ve made my point clearly.

Please, my friends. Before you decide this is not your fight, read, research, learn. Our shared future is at stake.

Recommended Watching

I’ve watched this memorial slideshow every year. It unfailingly moves me to tears. Never forget that day, nor misremember. Never forget those we lost, the heroes who ran unbidden toward danger and lost their lives saving others, the heroes aboard Flight 93 who lost theirs preventing another attack that would likely have killed scores more of their fellow citizens…

Inside 9/11: an in-depth accounting of the 9/11 attacks and the events that led up to them

102 Minutes that Changed America: a uniquely composed account of the attack on New York, seen through raw footage from a variety of sources, combined with emergency calls and radio communications

Recommended Reading

Of all the deeply moving posts, pages, and articles I’ve seen about 9/11, this one from 2009, comprised of stirring photos and an unflinching examination of the enemy and cultural crisis we face, is unforgettable and not to be missed: 9/11: Never Forget, Never Give In

I’ll also be posting links, separately over the next few days, to the best writing about 9/11 I encounter this year. Look for posts tagged “9/11”.

My Previous Years’ Posts

2009: Tomorrow is 9/11 ~ My Experience of September 11, 2001 ~ 9/11 Quotes

2008: 9/11, Seven Years On ~ 9/11, Seven Years On, Part 2 ~ 102 Minutes that Changed America

2007: 9/11, Six Years On

2006: Soon, Time Again to Reflect ~ 9/11 Observances ~ 9/11 Observances, Part 2

2005: I Remember

2004: Remembering and Rebuilding (Yes, that’s me, in a post at my old blog. I’ll be transitioning to blogging openly under my own name here shortly. It’s about time.) Republished here, September 12th, 2014.

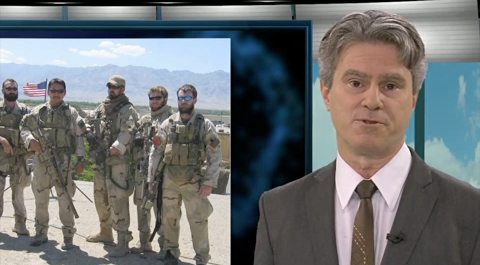

Who else but Bill Whittle can so adeptly weave together the early history of commercial aviation, this month’s deadly Chinook crash involving members of SEAL Team Six, the end of the Space Shuttle program, the private space race, the November 2001 crash of American Airlines flight 587 in Queens, and the needless, gut-wrenching destruction of the recent London riots.

Don’t miss “The Deal”, Bill’s latest Afterburner, on PJTV:

I would add one minor adjustment, that I doubt Bill would quibble with: To me, it’s being willing to risk dying for something that’s the key. Excepting one who chooses to embrace certain death as the last and only possible way to save others (as a soldier diving on a grenade, using his body to prevent the deadly spray of shrapnel from killing his comrades-in-arms), in a culture that rightly celebrates and cherishes life, we achieve our ends by embracing risk and seeking to live through danger, not by dying. Dying is just what happens the one time the gamble doesn’t pay off, despite our best reasonable efforts to prevent it short of playing life safe and never daring to venture anything at all (which is an end far worse than dying in the pursuit of a meaningful goal).

Amazon has Ernest Gann’s “Fate is the Hunter” in paperback.

UPDATE 2021-01-29: Thanks to BillWhittle.com member Jack R. for reminding me about the Wayback Machine! Scattered copies of Bill’s essays exist around the web if you search for them by title, but there’s also a complete archive of ejectejecteject.com here.

UPDATE 2016-04-17: As of a while ago, “Eject! Eject! Eject” went completely offline, with no clear word yet from Bill on what happened or if/when its content will be back. Bill’s “Silent America” essays are still available on Amazon in print form, and there is a copy of “You Are Not Alone” here. We’ll have to make do with those for now. Here’s hoping we’ll see the full catalouge of his superb essays republished again. Their insight and ability to uplift are timeless.

UPDATE 2012-05-25:Fantastic news! “Eject! Eject! Eject!” is back on the air — and, with it, every single one of Bill’s superb “Silent America” essays, including the long-lost (except in print form) History, Victory, Magic, Responsibility, Strength (including Part 2), Deterrence (complete with its Part 2), Sanctuary (yes indeed, dear readers, there’s a Part 2 too!), and Power!

Here’s an updated list. Please disregard the list further below that I’ve crossed out.

- Honor – December 22, 2002

- Freedom – December 22, 2002

- Empire – December 27, 2002

- War – January 26, 2003

- Courage – February 15, 2003

- Confidence – February 23, 2003

- History – March 29, 2003

- Victory – April 27, 2003

- Magic – June 7, 2003

- Trinity, Part 1 and Part 2 – July 4, 2003

- Responsibility – August 20, 2003

- Power – October 1, 2003

- Strength, Part 1 and Part 2 – May 22, 2004

- Deterrence, Part 1 and Part 2 – October 6, 2004

- Sanctuary, Part 1 and Part 2 – May 18, 2005 (not part of first print edition)

- Tribes – September 5, 2005 (not part of first print edition)

(ps – Try setting your browser to ISO Latin 1 encoding If, like me, you see ‘?’ placeholder characters where much of the punctuation should be when viewing some of Bill’s essays. For Safari, this is “View” -> “Text Encoding” -> “Western (ISO Latin 1)”. Bill’s site is mis-declaring the content as UTF-8. Oh well. You can’t have everything.)

From previous incarnations of this post:

Bill Whittle’s incisive “Afterburner” PJTV editorials have brought his sharp thinking to a whole new audience, but it was Bill’s brilliant and uplifting writing on the history, character, and spirit of America that I and many others first encountered. Bill’s superb essays — which he published first online at ejectejecteject.com, and later in print under the title “Silent America” — lifted me up when I needed it most, and are far and away some of the very best writing about this precious American civilization of ours that I have had the good fortune of encountering.

Since I often find myself recommending Bill’s “Silent America” essays, and since attempts to do so are bedeviled by the fact that many did not survive Bill’s move from ejectejecteject.com to pajamasmedia.com/ejectejecteject intact, I’ve compiled a list of them, with links to the ones that made it over. Thankfully, Bill has begun republishing them one by one at his new Pajamas Media address, and I’ve linked to the newly published copies where available. The “Silent America” essays are, in order:

- Honor – December 22, 2002

- Freedom – December 22, 2002

- Empire – December 27, 2002

- War – January 26, 2003

- Courage – February 15, 2003

- Confidence – February 23, 2003

- History (broken) – March 29, 2003

- Victory (broken) – April 27, 2003

- Magic (broken) – June 7, 2003

- Trinity, Part 1 and Part 2 – July 4, 2003

- Responsibility (broken) – August 20, 2003

- Strength, Part 1 (broken) and Part 2 (broken) – May 22, 2004

- Deterrence, Part 1(broken) and Part 2 (broken) – October 6, 2004

- Sanctuary (part of second edition only), Part 1 (broken) and Part 2 (broken) – May 18, 2005

- Tribes (part of second edition only) – September 5, 2005

- Power (broken) – October 1, 2003

Unfortunately “(broken)” means there’s almost nothing there to read. Most of these essays are truncated after the first few sentences or words. I’ll come back and update these links as each essay is, hopefully, republished. Meanwhile, the previous, “(broken)” links are just for reference.

There is, however, hope! You can buy the complete set of essays in book form on Amazon, which I can almost guarantee you’ll want to do after sampling Bill’s unparalleled wares.

Bill, by the way, can be found on Twitter as @BillWhittle.

Also, here’s a link to all the blog posts where I’ve quoted or mentioned Bill’s writing.

Enjoy!

Previous updates to this post:

UPDATE 2010-09-06: I’m delighted to report that one of Bill’s very finest essays, “Trinity”, is now back online. Don’t miss it. Thanks to reader David B. for sending the updated links!

UPDATE 2010-09-09: Freedom is back up too! (Thanks again to David B.!)

UPDATE 2011-04-30: Sadly, pajampajamasmedia.com/ejectejecteject started returning blank pages recently. I have an email inquiry out to the site admins about whether the Eject! Eject! Eject! archives can be brought back. Meanwhile, all of the following links are currently non-functional. I’ll try to keep on top of the situation and update this post when it hopefully improves. Thanks for visiting!

UPDATE 2011-08-13: I just noticed pajampajamasmedia.com/ejectejecteject is back online, and the above Silent America essay links appear to be working again!

I’ve made a habit, for some years now, of collecting quotes that strike me as profoundly insightful or interesting, probably for all the same reasons that others do — for the keenly focused insight and concise expression of ideas they offer, as well as the inspiration and distilled wisdom they can call to mind on a moment’s notice.

Having recently sifted through the assortment of text files where I’ve been gradually stashing these hand-selected quotes away, I’ve assembled the best of them into a new “Quotes” page that I invite you all to visit.

The topics include Liberty & Economics, Cultural Confidence, War, and keeping Perspective. I hope my readers will draw as much enjoyment from them as I have.

UPDATE 2010-02-08: I’ve added several more selected gems, dug out of a handwritten journal I’ve kept off and on since September 2002. Enjoy!

One nagging thought that’s troubled me for several years now has concerned the nature of “frontiers” — the character of those who strike out to populate them, what happens as the populace of a former frontier changes over time, and what to do when we run out of new frontiers to settle.

The United States began life as a frontier of far-flung colonies — colonies that came to be populated by people who were brave, bold, and/or desperate enough to give up every semblance of stability in their former lives and risk everything on the possibility of a new and, they hoped, better future on the other side of a formidable ocean — a future they knew full well they would have to fashion by their own exertions, at considerable risk, in a land of many unknowns.

Over the few centuries since, the US has become a new home to immigrants with similar circumstances, motivations, dreams, courage, and drive hailing from every reach of the planet. Many more who might have wished to begin new lives here, but were fearful of the risks this life entails, did not come, and in this way our melting-pot population became a self-selecting group largely characterized by a measure of boldness, guts, and — I dare say — genuine, honest-to-gosh audacity.

At the same time, of course, we’ve also set about increasing our ranks the old fashioned way. Those born here sometimes successfully absorb the spirit of the place, and grow up to share such courage, determination, independence, work ethic, and mettle as their immigrant ancestors bore. Others somehow don’t acquire these traits, and seeing as they’re already here, don’t have to get here, and typically stay, they end up edging our average bearings as a population a bit farther away from that rugged pioneer spirit.

Roughly speaking, then, relative rates of immigration and birth, coupled with our rate of success or failure at instilling a love of sweet Freedom in our newly minted Americans, combine to determine the vitality of the American Spirit. (I leave out emigration as a relatively insignificant contributing factor because — funny thing — that just doesn’t happen much here.)

This all leads me to a question that, to my scientifically-trained mind, is reminiscent of the grand cosmological question of whether we live in an “open” universe (one that will continue to expand without limit) or a “closed” universe (whose expansion will eventually be slowed and then reversed by mutual gravity, leading it to recollapse):

Does a frontier inevitably move?

Maybe the answer should be intuitively obvious. A frontier doesn’t stay a frontier forever. New places are discovered, and become the new frontiers, while the old, now-familiar places accumulate a sort of inertia and become stable.

Only, what happens when we run out of new places? What happens when the old, former frontiers become gradually less friendly to those who dare to dream the really big dreams, who aspire to wide-open unencumbered FREEDOM as far as the eye can see, but there’s nowhere else left for them to go?

Barring the discovery of an unforseen loophole in the laws of physics as we’ve thus far distilled them, we are prisoners of our own solar system, whose eight — er, strike that — seven other planets aren’t particularly hospitable to human habitation. At great cost and with enough of the hardy pioneer determination that birthed this nation it could be done, perhaps, but there is no other home remotely as cordial as this precious blue-green marble we inhabit within our grasp. Firefly fantasies aside, enterprising interplanetary homesteaders don’t have a whole lot of choices — or, really, any — right now.

This fact has been keenly on my mind as we watch our beloved United States of America become seemingly less and less recognizable to those of us who prize untrammeled individual freedom as the Founders did. As our population gradually loses that once-indomitable frontier spirit, and in the place of cherishing Sweet Liberty increasingly demands the safety, security, and closing of material equality gaps that are promised by a culture of regulation, entitlement, and coerced redistribution, so our dear country begins to seem less and less the kind of place for an intrepid frontiersman or frontierswoman to hitch their wagon to.

Perhaps the strangest thing of all about this “Europeanization” of America is the insistence on implementing such ideas here, despite the litany of nations in which they are already practiced (a fact it seems we’re incessantly reminded of by domestic critics of the classically American Way of life — you know, the ones who insist that Swedes, Venezuelans, and Cubans are somehow “freer than we are”). “Diversity” is not so much to be sought and celebrated, it seems, when it comes to socioeconomic policy — at least when doing so favors the continued existence of classically liberal (economically permissive rather than socially engineered) societies. Oddly, though the United States places no restrictions on emigration, proponents of Europeanization rarely seem to choose that route to obtaining the lifestyle they favor. There is something about this drive that seeks to transcend personal choice and impose that choice on others (ostensibly for their own good, of course).

Maybe the subduing of America is a “Holy Grail” of sorts for those who aspire to bring the benefits of benevolent statism to the whole world. Transnationalism has been a key aspect of Marxism from the get-go, and some ideas die hard. Today’s transnational progressivism, with its contempt for and active attempts to undermine international tax and regulatory competition, seems little different in this respect. Transnationalism seeks to seal off all avenues of escape for those who crave and seek greater economic freedom and commensurate responsibility for assuming risk. There would be no way out in a future world that agrees on and enforces the same set of laws, taxes and restrictions everywhere. The message from control-hungry transnationalists is clear: Tough luck, buddy. One Vorld Government vill be gut, und you vill like it.

If even the fiery, fiercely independent souls who inhabit the United States can be berated into giving up Liberty for safety, superficial equality, “fairness”, “niceness”, or just to be like everyone else, then there is truly no limit to statism’s ability to dominate a willing, submissive, or even just indifferent humankind. If we choose — on a personal, individual and not just national level — to continually seek the approval of others in an exceedingly self-conscious high-schoolish popularity contest, in the place of cherishing our right to scandalize the neighbors, then we are as good as done, and the American Idea is dead — much to the delight of its very vocal detractors.

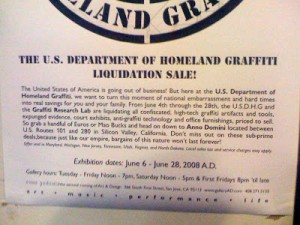

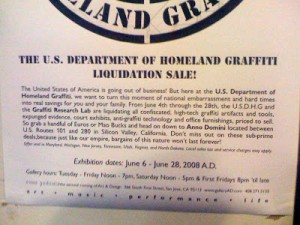

Take a good look at the following piece of contemporary art, which I took notice of among the 2008 “Zero1” exhibits in San Jose. Study it until you see the message behind the message.

In the final year of the Bush administration, this was shown as mockery and criticism of America’s conduct in waging the Global War on Terror, from the perspective of the sort of person who thinks we ought to be ashamed of ourselves rather than fiercely proud and doggedly committed to our nation’s defense in the wake of the 9/11 Jihadist attacks on US soil. The longer I studied this image, the more the eagle’s tear rang hollow. Is the artist’s intent really to express regret at the decline in opinions of America that he or she obviously feels is justified?

I think there’s a clear second meaning here, that’s picked up by those who go in for such stuff, and it is one of triumphant celebration. There are people — the artist included, I strongly suspect — who could not be more pleased by this development, who don’t merely feel ashamed of what they think we’ve become, but cannot stand even what we once were and have long stood for, and who cannot wait for the American Idea itself — the notion of your life on your terms — to fall in the world’s esteem, lose its luster and appeal, and fade away as an object of aspiration for millions upon millions the world over. They want mindshare for governing ideas of their own, and those ideas have little to do with freedom I’m afraid.

Friends, it’s no accident that the tongue-in-cheek “fire sale” that this exhibit advertised accepts “Euros or Mao Bucks”:

Why is it that we keep seeing these folks among the ranks of anti-war activists? It’s hard to avoid supposing that they are more accurately pro-war, but on the other side.

Look at the image again.

It is not a lament, but a victory banner. Those it speaks for feign disappointment, but in truth couldn’t be more pleased. America and what she represents falling in the world’s esteem. Mission Accomplished.

These fellow citizens and others like them aim to demoralize us with their moralizing — to tame, subdue, and crush the defiantly independent frontier spirit that makes us us — and I fear they may be succeeding.

How we got to this point from our ruggedly independent, defiantly freedom-loving, living-my-own-way who-cares-what-others-think frontier roots is a very long story. But the net change in our national character could hardly be more pronounced.

Living in the far-West former frontier “Gold Rush” state of California as I do, I feel acutely aware of the especially radical transformation my state has undergone since its settlement — crossing the full spectrum from initially wild and lawless open country to one of the most social-engineering-heavy and burdensomely taxed and regulated (or, if you prefer, most “progressive”) states in the Union. To some, this is desirable progress. To me, it is the slow, tragic dying of a cherished dream and ideal.

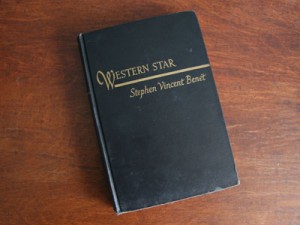

When I contemplate the Frontier, the “Invocation” of Stephen Vincent Benét’s epic poem “Western Star”, which I first mentioned a few years ago, always comes to mind. I’ve read this passage at home in far-West California; I’ve read it on vacation on a horse ranch in Wyoming, a state whose wide-open vistas preserve some of the last remaining fragments of the old frontier spirit. And it gives me a deep shiver. Every time.

Not for the great, not for the marvelous,

Not for the barren husbands of the gold;

Not for the arrowmakers of the soul,

Wasted with truth, the star-regarding wise;

Not even for the few

Who would not be the hunter nor the prey,

Who stood between the eater and the meat,

The wilderness saints, the guiltless, the absolved,

Born out of Time, the seekers of the balm

Where the green grass grows from the broken heart;

But for all these, the nameless, numberless

Seed of the field, the mortal wood and earth

Hewn for the clearing, trampled for the floor,

Uprooted and cast out upon the stone

From Jamestown to Benicia.

This is their song, this is their testament,

Carved to their likeness, speaking in their tongue

And branded with the iron of their star.

I say you shall remember them. I say

When the night has fallen on your loneliness

And the deep wood beyond the ruined wall

Seems to step forward swiftly with the dusk,

You shall remember them. You shall not see

Water or wheat or axe-mark on the tree

And not remember them.

You shall not win without remembering them,

For they won every shadow of the moon,

All the vast shadows, and you shall not lose

Without a dark remembrance of their loss

For they lost all and none remembered them.

Hear the wind

Blow through the buffalo-grass

Blow over wild-grape and brier.

This was frontier, and this,

And this, your house, was frontier.

There were footprints upon the hill

And men lie buried under,

Tamers of earth and rivers.

They died at the end of labor,

Forgotten is the name.

Now, in full summer, by the Eastern shore,

Between the seamark and the roads going West,

I call two oceans to remember them.

I fill the hollow darkness with their names.

Is it possible to read the above and not feel it in your bones?

All this has been on my mind for a seemingly very long time now, but it took this superb blog post by “VodkaPundit” Stephen Green to prompt me to finally compose my thoughts.

American freedom was a huge, sprawling, messy, brawling thing. It consumed everything and anything, and spewed out an unimaginable bounty. For some, the freedom was about growing their business and making money. For others, it was about growing their hair and making love. But it was always here, for anyone willing to risk the journey and leave behind the Old World and its old ways.

But now that we have this wonderful place, this precious idea — what are we doing with it?

Already, the government runs our children’s education and our parents’ retirement. Now we’re allowing it to usurp our banks and nationalize what remains of our auto industries. Within weeks, Washington promises a plan to dictate our health care. To do all this, we’ve let Washington run up enough red ink to impoverish our grandchildren. As if all that weren’t enough, the president still found the time to kick our friends in London and Tel Aviv while courting a genocidal, election-stealing maniac in Tehran. He even gave a speech in Cairo — that oppressed, impoverished Old World megalopolis — in which he assured the world that America really is no better than anywhere else.

Well, once upon a time, we were.

Absent a warp drive, a wormhole, or some other science fiction escape to an uninhabited Earth-like planet, it’s impossible to recreate the conditions which allowed the creation of these United States. It can’t be done; there aren’t any New Worlds left to discover. Our maps are all filled in.

If the Old World comes here, where does the New World have left to go?

When the Puritans were persecuted in England, they risked everything to come to America. When young Germans faced the Prussian army’s grip, they gave up their ancient towns to come here. When Jews faced the Czar’s pogroms, they gave up their bucolic steppes for the slums of New York. Rather than accept stagnant lives in their own countries, Latin Americans risked uncertain lives in America. Rather than accept far milder impositions than our own, America’s Founding Fathers risked their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor just to sign their names on parchment.

Anyone with nothing to lose and everything to gain — and bearing wits and character enough to risk it all — came here. They ventured here. To America.

Whatever liberty we have right here, right now, in America … well, for all practical purposes, that’s all that’s left anywhere. If France had our freedoms, there would be no French here. If China had it, there would be no Chinese here. If it existed in Latin America, there would be no Spanish spoken here. And so it goes.

And so if we, here in America, throw it all away in a fit of panic or pique, then what we once called “America” will become as false as a fairy tale.

By all means, read the whole, brilliantly worded thing.

One more thought in closing:

Remember the 2004 and 2008 presidential elections, when many on the left threatened to “seek asylum” in Canada if Bush or McCain won?

Those of us who cherish the classically American commitment to individual Freedom have no Canada. America is our last, best hope. Our opponents know it. And if we lose this ground for good, it seems to me we will have lost everything that matters.

For the sake of all we hold dear in this life, we mustn’t let that happen.

This Wall Street Journal piece by Charles Murray went by a few months ago, but is such an excellent bit of writing that I’m belatedly posting about it as I meant to back then. “Europe Syndrome” is well worth reading in its entirety, but here’s a highlight.

I, for one, am an American Exceptionalist at heart — so grateful to have had the good luck to be born right where I belong. I often fear we are a dying breed. We must figure out how to keep the shining beacon, the defiantly individualistic spirit of American Liberty aglow.

American exceptionalism is not just something that Americans claim for themselves. Historically, Americans have been different as a people, even peculiar, and everyone around the world has recognized it. I’m thinking of qualities such as American optimism even when there doesn’t seem to be any good reason for it. That’s quite uncommon among the peoples of the world. There is the striking lack of class envy in America—by and large, Americans celebrate others’ success instead of resenting it. That’s just about unique, certainly compared to European countries, and something that drives European intellectuals crazy. And then there is perhaps the most important symptom of all, the signature of American exceptionalism—the assumption by most Americans that they are in control of their own destinies. It is hard to think of a more inspiriting quality for a population to possess, and the American population still possesses it to an astonishing degree. No other country comes close.

Underlying these symptoms of American exceptionalism are the underlying exceptional dynamics of American life. Alexis de Tocqueville wrote a famous book describing the nature of that more fundamental exceptionalism back in the 1830s. He found American life characterized by two apparently conflicting themes. The first was the passion with which Americans pursued their individual interests, and made no bones about it — that’s what America was all about, they kept telling Tocqueville. But at the same time, Tocqueville kept coming up against this phenomenal American passion for forming associations to deal with every conceivable problem, voluntarily taking up public affairs, and tending to the needs of their communities. How could this be? Because, Americans told Tocqueville, there’s no conflict. “In the United States,” Tocqueville writes, “hardly anybody talks of the beauty of virtue… . They do not deny that every man may follow his own interest; but they endeavor to prove that it is the interest of every man to be virtuous.” And then he concludes, “I shall not here enter into the reasons they allege… . Suffice it to say, they have convinced their fellow countrymen.”

The exceptionalism has not been a figment of anyone’s imagination, and it has been wonderful. But it isn’t something in the water that has made us that way. It comes from the cultural capital generated by the system that the Founders laid down, a system that says people must be free to live life as they see fit and to be responsible for the consequences of their actions; that it is not the government’s job to protect people from themselves; that it is not the government’s job to stage-manage how people interact with each other. Discard the system that created the cultural capital, and the qualities we love about Americans can go away. In some circles, they are going away.

…

The possibility that irreversible damage will be done to the American project over the next few years is real. And so it is our job to make the case for that reawakening. It won’t happen by appealing to people on the basis of lower marginal tax rates or keeping a health care system that lets them choose their own doctor. The drift toward the European model can be slowed by piecemeal victories on specific items of legislation, but only slowed. It is going to be stopped only when we are all talking again about why America is exceptional, and why it is so important that America remain exceptional. That requires once again seeing the American project for what it is: a different way for people to live together, unique among the nations of the earth, and immeasurably precious.