I’m a “rah, rah America” guy. I can’t help it. Ever since I can remember, I’ve felt an appreciation and natural affection for this way of life of ours here in the USA, with its steadfast foundational devotion to Liberty. What I would call a deeper gratitude likely came later, as I’m sure I took this precious inheritance for granted growing up, and had little idea it would ever truly be in jeopardy. The ever-present threat of a nuclear attack by the Soviet Union loomed large during the 70s and 80s, but I found reassurance in the cultural resolve I perceived all around me. We seemed sure of who we were and of the imperative to stand and defend this way of life. It was precious and worth every measure of devotion, so much so that even a fearsome and dangerous external enemy did not in the end seem more than a serious but likely manageable concern that we’d do everything we could to guard against. I had no idea, back then, that our foundations were under sustained internal attack, or that our undoing could ever possibly come from within rather than from an external adversary. The possibility just wasn’t even on my radar.

Growing up in this environment, I never anticipated, much less understood, the desire of some to live in a collectivist society, even as some abstract ideal. It seemed obvious to me where that road led — that it was a sure-fire recipe for subservience to an abusive, totalitarian state, and that there was no more certain way to extinguish creativity and the potential for thriving that make life worth living. Striving for independence and the life of a free individual was clearly worth it, even with the attendant uncertainty and risk. The only way I ever imagined that people would submit to collectivism was unwillingly, under the thumb of a totalitarian reign of terror like that which prevailed in the Soviet Union and its captive satellite nations, in China, or in North Korea. It interested me to learn the stories of people who had escaped collectivist societies, and also how those who chose to remain or were unable to escape found ways to cope, endure, maintain perspective, and push in whatever ways they could to move things back in the direction of freedom. Traveling to the Czechoslovakia of 1986 (where we had family who feared the peril they’d face when the state learned they’d met with Americans, including a cousin we never got to see who we later learned was sent to a forced-labor camp), and awareness of Soviet dissidents such as Sakharov, Sharansky, and Solzhenitsyn, reinforced my interest in understanding the way out from such things. Encountering Americans who expressed an affinity for or aversion to criticizing collectivism, later in life, was an experience for which I was wholly unprepared, and stands to this day as about the most chilling realization of my life. If, after every purge and totalitarian horror of the 20th century, there are people who still yearn to bring about a move to collectivism in some form, and if those people can gain the levers of power and cultural influence in so steadfastly, defiantly free and independent a place as the United States, then there seems to be no limiting factor on the horror that may await us in the future yet to come.

These worries bring me gloom sometimes, and the eager, enthusiastic embrace of appeals to authority we’ve seen in the COVID years has only deepened my concern. But I can’t allow myself to live in that gloom. Such is not the purpose of life in this world — one imperiled by our self-destructive will to subservience, to be sure, but also too full of hope for many to grasp. I can’t make choices for others, nor would I wish to, but I can choose my own actions and attitude, and the thoughts I populate my world with. Even as the slow creep of incrementalism seems to march inexorably on, I see glimmers of an inextinguishable desire to live free and thrive, and tremendous hope in the prospect of opening new frontiers and decentralizing ourselves away from the ossified institutions that are holding us back from the fullness of what we can achieve. I’m going into the future with this thought and the goal of realizing it in mind. I have faith, in the end, that we will find our way.

People can be tricked into accepting, in repeated small increments, massive changes that they would never have put up with all at once. This appears to be true of both individuals and entire populations. It’s a fact of human nature that I suppose is the darker side of our characteristic adaptability, and appears to have been instrumental in reaching the sad state I find us in. This phenomenon has been on my mind in recent years, perhaps because I’ve now lived long enough to witness the long arc of its consequences and see how much of our condition it appears to explain.

We in the USA are both blessed and perhaps cursed to be a remarkably accepting, easygoing culture. This assertion runs contrary to the oft-repeated slanders that we are cruel and intolerant, but it is demonstrably true. How else could we reach a point where we’ve allowed nearly every institution to be slowly but steadily turned against us, infiltrated by people bent on the systematic dismantling of our foundational values and the very essence of who we are? The trope of insufficient tolerance and kindness will continue to be leveled against us, precisely because our good nature abhors and recoils from such accusations, causing us to capitulate with muted objections, one small increment at a time. The trope is employed, because it is effective, because we are kind.

If there is a limiting factor to the cumulative damage such incrementalism can inflict, it may be impatience. Some can’t help but want to push this transformation faster, even when things are going their way in the long term, and in their moments of eager overreach they eventually push us too far all at once. The threshold of our easygoing nature is exceeded, and we become alerted to what is going on. We are living in a time of sustained impatient overreach that seems to have crossed the line of acceptability for many. My own personal line has certainly been crossed. I expect this to inject some salutary feedback into phenomena that have been trending badly for far too long, but it remains to be seen whether that will be enough.

I was raised by two loving parents, in a better time for which I am deeply grateful, to live with integrity and virtue in a world that no longer exists. The world that has supplanted it is decidedly done with me and those who share my values, and the feeling has become mutual. My parents’ passing in 2016 and 2020 feels like a key inflection point in that conclusion, taken together with the realization that my sons are now old enough that they will start to be impacted by the wounded state we’re in. I’ve been an easygoing guy all my life, but I can no longer accept and accommodate things that are toxic to my nature and threaten my children’s future. Now is the time to draw the line and stand for my convictions, against cultural tides that mean harm to all that I love, buoyed by the gift of the better world I have seen and know is possible, and deep gratitude for having known it. I’ll be walking with greater resolve toward the metaphorical battles that must be fought, to save the future I hold dear, and I expect to be thinking, writing, and publishing more here and in my other outlets in pursuit of that.

It’s been on my mind to do some more writing and podcasting — a thought that has me pondering both the content I want to get down in words, and the potential purpose of completing and publishing that work. I’ve gained a lot of valuable and life-improving perspective in recent years, that I think could be of help to others who may be journeying down similar paths. It interests me to distill my observations — partly for my own use in developing my thinking further, but I also wonder to what extent it may be a worthwhile endeavor to publish the results, either here or elsewhere.

With time being in short supply relative to my many projects, I'm driven to weigh the value of this endeavor as realistically as I can. To what extent will it matter? I think of all the superb writing that's already out there on the subjects that preoccupy me, by writers whose wonderfully articulate insight both inspires and humbles me (see my links page for some of my favorites), and I have to wonder whether the most useful thing I can do is direct people to their work. Twitter is an apt and effective tool for that, and a substantial part of my use of it (as well as this blog) has been for that purpose. Where others have said with great clarity of thought what I have lacked the talent and time to articulate, it makes every bit of sense to direct people to their articles, podcast episodes, and videos with due enthusiasm.

Time is in understandably short supply for potential readers, too. In a world where Twitter's brevity connects people with ideas, and with one another, with undeniable effectiveness, I make the time to read my own favorite writers far less often than I'd like to. What are the chances that others will find the time to read my own humble work, or can be reasonably expected to? At the point of that thought, I fall back on the knowledge that putting my thoughts together in writing is of great benefit to me, independent of how many or few others may read or benefit from the results. But if I'm going to take the time to craft work that I'm happy enough with to publish, and because I harbor hope of helping others and building friendships with people on similar journeys, I feel driven to figure out what I can do that would be most effective and worthwhile.

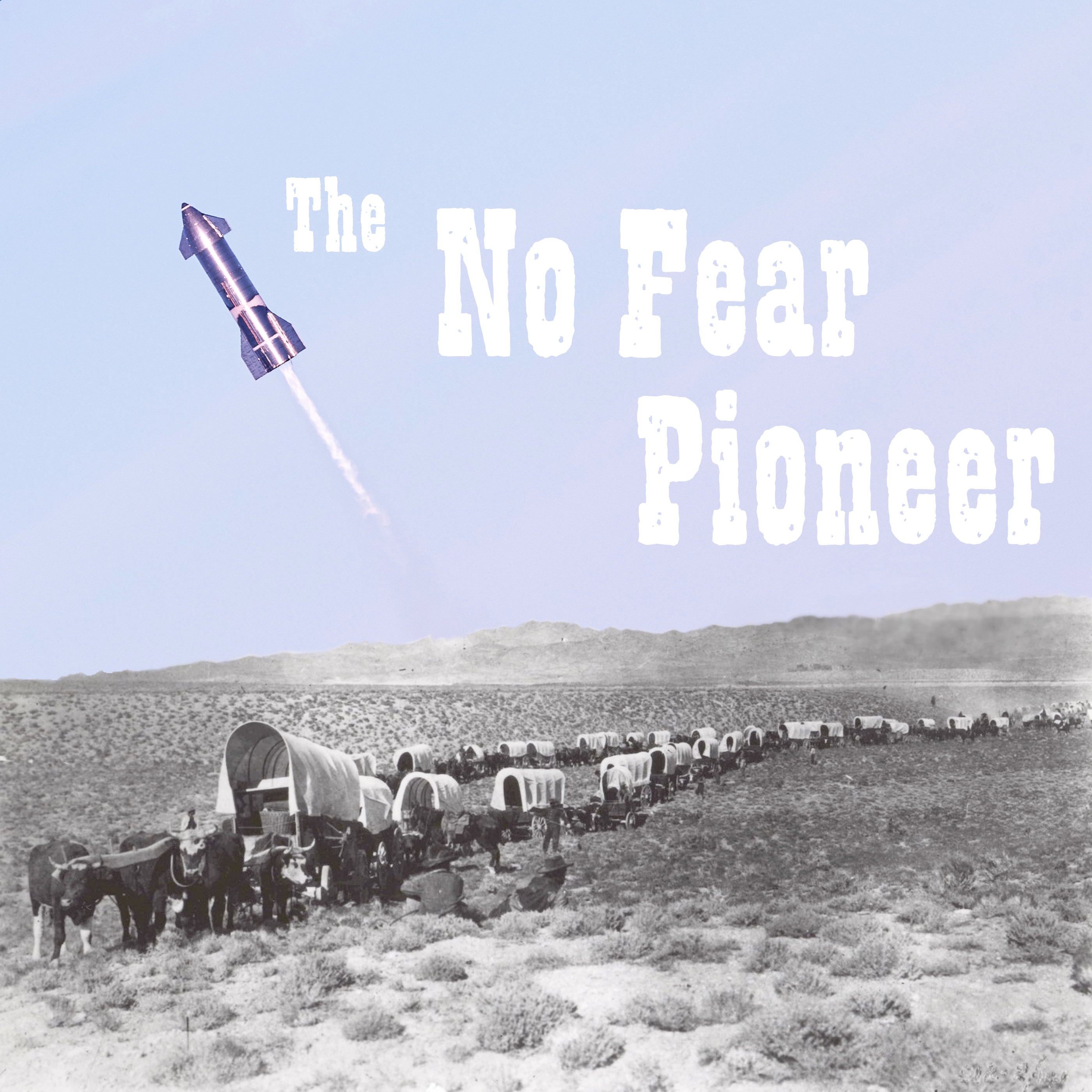

They say to write about what you know, and maybe therein lies the answer. More specifically, I think I need to figure out what I can contribute that's relatively unique — what's a novel result of my own perspective that might not be found elsewhere. My thinking about the frontier cycle and the development of new frontiers seems likely to be part of that, and I may redouble my focus on that pursuit both here and on the No Fear Pioneer podcast. I'll be interested to see where that goes, and I hope others will find some value in the results of these pursuits too.

As always, I'm figuring it out as I go…

This will be the first Mother’s Day without my Mom, who passed away last July. It’ll be the first time I can’t send her flowers and a card, or call her up and wish her a happy one, or thank her for all her boundless love and caring and kindness over the years, or remind her how much I love her and how much she means to me.

Mom’s final stage of decline was fairly fast, but she spent a lot of time before that in sort of a “plateau” that I’m relatively grateful for, where her Alzheimer’s symptoms seemed to progress only very slowly. Sixteen months ago, she had forgetfulness and confusion, but she could still laugh, talk, smile, and walk about with a little help. We spent Christmas of 2015 together, Mom chuckling approvingly from the sofa as her grandchildren played at her feet. A month later, she was bed-bound and much less communicative, and shortly after that it became clear that my 89-year-old Dad could no longer care for her at home, even with help. They moved into an assisted living facility just a few months before she passed.

I worry about Dad now. Thankfully, he’s always been an optimist who is very good at finding the bright side, keeping busy, and carrying on. We speak often, and he seems to be managing fairly well. But I can only imagine how much he misses her. Loss of one’s spouse is a weighty thing that I can scarcely begin to fathom. I’m heartbroken all over again, just contemplating this Mother’s Day, and revisiting old pictures and my post from Mom’s passing last year. Treasure the time while you have it, my friends. And make sure to care for those left behind.

This Saturday, we held a memorial service and reception in honor of my mother, Gabrielle Stephens (née Stransky), who passed in her sleep early in the morning on July 18th, as the final act in a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease. My father, the most loyal companion anyone could have, cared for her at home for as long as he could, then remained by her side in assisted living until the very end. My sister and I had been traveling to visit them monthly, and I’m grateful that we had enough advance warning to spend her last two days together with her.

My Mom was born and raised in the small rural town of Bogros-Messeix, in the Auvergne region of central France, and I remember her as a generously happy person. She found joy in the world, and seemed to want more than anything to share it with us — which she managed to do the moment you saw her. She always had a smile to greet you with, and it was impossible to be or remain gloomy in her presence. Her laugh, that I know all who knew and loved her can still hear, and her delight in little things, were absolutely contagious.

Being gracious and hospitable was tremendously important to my Mom, and came to her naturally, as it did to our dear aunt, her sister Marie, and her restauranteur husband Raymond. Growing up alongside their daughters, Raphie and Zizi, we enjoyed the extraordinary circumstance of our families living near one another in West Los Angeles, and making a point of getting together often — a situation whose rare preciousness I can only now truly appreciate. Marie and Gaby took turns hosting Thanksgivings, Christmases, and Easters, bringing together not just our two families, but also longtime friends from the French community, who became a true part of that family. Those lively gatherings were full of a kind of warmth and gracious delight in one another’s company that I wish everyone would get to experience in some form in their lives. Those times seem far away now, but they will always be with us. And we are reminded to strive to carry on what these sisters and their husbands so skillfully and lovingly began.

Gaby’s parents had emigrated to France from Czechoslovakia, and I don’t know whether many French ever considered her and her family truly French, but to the adoring parents she effortlessly charmed at our elementary school, her credentials as a sophisticated, delightful Frenchwoman were beyond question. My Mom briefly taught a French language class in the library for some of the children. In going through things, I found we still have her extensive notebooks and handwritten flash cards from that project, where she jotted down phrases and translations and details of grammar that she must have had to research well beyond what she’d had the chance to learn in her short schooling. She did it all with great joy. And those lucky kids got to taste the world’s best homemade crêpes, too.

Though timid about some things, my Mom could have a surprising sense of adventure and willingness to try, or be talked into, new things. I remember one particular afternoon, spent with Dad’s family on Deer Creek reservoir in northern Utah. We somehow managed to get my Mom on a Jet Ski, without explaining that gripping the handles for dear life also squeezes the throttle full open. Fortunately, the time for her to leave us was not yet.

Mom arrived in the United States by boat in 1952 — sailing into New York Harbor on the Ile de France to join Marie and Raymond in Chicago. The three worked there as house servants for a time, before moving to Palm Springs, where she met and married her first husband. When his his postwar Army service as a chef to Allied officers took them to Paris, Mom enrolled in esthéticienne training.

On their return to the U.S., Mom put her new skills to use in a successful career at the Beverly Hills salon of Aida Grey. After they divorced, she opened her own salon, which as luck would have it led to being introduced to my Dad by one of her adoring clients. They met and married in 1968.

I’m the second of Mom and Dad’s three children. Veronique, the big sister we never had the chance to know, was born two months premature and never managed to take a breath. Dad is working on reuniting her remains with theirs.

I remember Mom’s occasional need to renew her status with the French consulate when I was a kid. When she decided to earn her U.S. citizenship, she studied hard for it. It must have been one of the bigger challenges my mother undertook. But she saw it through, and we were as proud to be there in support of her at the swearing-in ceremony in 1990 as she very clearly was to have achieved it, and to have formalized the affectionate ties she already felt toward her adopted country.

Mom worked hard for us, diligently and without ever slowing down or giving up. She toiled and sacrificed, so that we could live well. She kept an impeccable home. She made sure we got to go places. She had our friends over. (Nobody ever left our house hungry.) She took us to the park, to the beach. She and Dad took us to Disneyland, Knotts Berry Farm, and the Sequoias. My Mom braved a terrifyingly short 3-lane change on the 10 highway in L.A., to get me to Saturday science camp at Exposition Park. I know that part of the drive terrified her and she dreaded it. But she overcame that fear. For us. She made sure we had a full and happy childhood.

The joy my Mom experienced in life, and her glowingly positive attitude, somehow survived the difficult years she grew up in. Her family lived through some lean and fearful times that are hard for us to fully appreciate today.

Mom’s family were of modest means. Her father, brother Emil, and brother-in-law Leon worked in “La Mine” — deep underground, in the town’s coal mine. Their father proudly and stubbornly endured work in waist-deep water, for attending the wrong church. For part of Mom’s childhood, their town in France was under Nazi occupation. She told us stories of living life under the watchful eye of German soldiers — men who gassed people in churches, men whose belt buckles read, “God is with us”, leading her to wonder: “If God is with you, then who will help us?” She remembered darting furtively through their garden in winter to dig up buried cabbages in the snow and bring them back to the house, worrying all the while that she was being watched. She remembered her mom carrying grenades in her apron, to bury them in that same garden. They belonged to her brother Emil, who was part of the Maquis — the French resistance — and she was worried they hadn’t been well hidden. You can imagine the family’s constant concern that they would be found out.

The war wasn’t the only hardship the family endured. Their mother, Bozena, an educated midwife who delivered most of the town’s babies, passed on September 1st, 1947, when Gaby was only sixteen — leaving her and her siblings, Marie, Elise, and Emil, to care for their father and one another. Bozena suffered from a heart ailment that ended up being made worse by her treatment, and as a result she was taken from her family too soon.

My Mom had sweet memories of growing up in Bogros too. The hills and woods where they played. Her father fishing, sitting on a boulder in the middle of the Dordogne. (That, more than anywhere, must have been his “happy place”.) “Chercher champignons” — Hunting for wild mushrooms in the woods. Gathering water at the fountain with her dear lifelong friend Emma Pavlovsky. The sweet smell of tangerines her mother had hidden under the stairs (a rare treat then), which my Mom always said was how they knew Christmas was coming.

Mom remembered her sister Marie sneaking sweet treats from the sugar bowl now and then. Her brother Emil famously helped with dental and electrical chores. (When one of them had a loose baby tooth that needed tending to, he’d dutifully tie a string to it, tie the other end to a doorknob, and … you can imagine step 3. When Emil needed to check whether the electrical outlets were working, a sister’s well-placed finger would do the job just fine.)

My Mom surviving all of that and making her way to the United States, and eventually to Los Angeles where she met my Dad, was a big stroke of luck for all of us. We lived many years there, in a life we were lucky to have.

I remember where I was, coming up our old back steps to the kitchen from playing outside, when Mom told me she’d had a phone call from France, and learned that her father had died after a battle with cancer. She said she had known it before she received the call.

In 2004, we lost my Mom’s sister Marie, who was brutally taken from us all far too soon. We all felt the loss deeply; Mom most of all.

With my mother’s passing last week, their sister, Elise — who lives in an assisted living home in France, attended by her daughter Dany — is now the last of the Stransky children. The world will never again be as bright, when they all are gone.

Alzheimer’s takes a person from you piece by piece, with heart-rending cruelty. By the time my Mom passed, I was already well down the road to missing her tremendously. But I’ll be eternally grateful for the beautiful life she got to live, for all the love and care that she gave us so generously, and for my father’s steadfast devotion and the undying love that kept them together to the last.

“You’re my sweetheart, and I’ll love you forever,” he said at the very end. I can’t think of a more beautiful way to say such a difficult goodbye.

My friends, it’s time for a new project — one that can no longer wait for me to get around to it.

I’ve journeyed through a lot of reflection in the years since I started to become aware of the decay afflicting our essential foundations, self-perception, and cultural confidence. I’ve worked through much of my thinking here and in my Twitter stream. It’s included no small amount of despair at the sometimes hopeless-seeming state of things — despair that I can only say has been made less lonely at least, thanks to the world-changing communications revolution we are living through and may in some ways only dimly appreciate. A burden shared is lightened, and all that. But in the past year or so, something very crucial has changed in my outlook. I’ve turned a corner, and been granted a new view of things, a new and more positive perspective. It’s not that I see the stakes as having lessened — for what’s at stake is truly nothing less than everything that matters most in this precious, hard-won Civilization we are so lucky to call home. Indeed, the stakes are as high as ever. The hour is late. The situation is dire. The outlook is grim. By God, it’s time to come out fighting! It’s game time, in the most important game you or I will ever be a part of.

I say that my outlook has become more positive, but it might not strike you as such. It has begun to seem entirely possible to me that the United States of America — this magnificent, precious outpost of Freedom that I have cherished all my life, that has stood through more than two centuries of history’s cruel challenges — may be on a one-way road to ruin by voluntary national suicide, with no real hope of a turnaround, and our closest friends and allies appear to be in no better shape.

Progressivism is a ratchet. The state’s dominion advances, the right to be left the hell alone is gradually diminished. Reversals of this natural tendency are rare and temporary, ultimately overwhelmed by the net vector toward more regulations and force and coercion, more meddling in our lives and purses. The Founders understood this, before the concept of Progressivism existed under its current banner. I’m only dimly catching up to the stark reality that I believe they saw all too clearly. Even when Liberty thrives, it is in constant danger from the more sinister aspects of man’s nature and aspirations — disguised, more often than not, behind the facade of a conveniently defined collective good.

I’ve lived most of my life believing strongly in our mission to help liberate people around the world who have not had the opportunity to know the blessings of liberty, and I still believe in that to great extent. Where there are people who truly yearn to be set free, such that they are willing to risk everything for it, I want to support them, in spirit and otherwise. But I have also come to see that there are large numbers of people in this world — far more than I had ever realized — who simply do not have a strong desire to be truly and meaningfully free, who in fact would rather like to discharge the various burdens that go with such freedom. There are many, many people who will gladly line up and ask the state to relieve them of their load of worry and insecurity about themselves and their futures, and either don’t feel diminished or don’t mind feeling diminished by the result. You and I (if I may presume), with our zeal for untrammeled Freedom and a culture that sings its praises from the rooftops, are the odd ones out, and will quite possibly never make sense to these others. We may also, in this time and place, be outnumbered.

Friends, I’m an optimist in my heart of hearts, and I don’t want to be one to declare that there is no hope, that the fight is lost and it’s time to abandon ship. This is a fight worth fighting. And in some sense it’s positively absurd that we should even have to fight it here of all places — that we should be expected to cede ground to a political belief system whose proponents like to point out that it exists just about everywhere else. The battle cry of “Diversity!” falls silent remarkably quickly, when it comes to allowing this rare and precious outpost of something different from the rest of the forsaken world to remain unique and different. Suddenly, it’s “why can’t we be more like everyone else?”. Zzzz… Are you kidding me? If I wanted that, I’d have emigrated, instead of choosing to make this land devoted to Freedom and living as you damn well please my home.

Make no mistake: It grieves me to see this. It’s a sad, pathetic end for a nation built by people bolder and braver than ourselves. But such are the mechanics of civilizational decline, it seems. Places meet their end. Ideas seek new frontiers and live on.

So let’s just suppose that everything we hold dear is collapsing in this place and time, and there’s next to nothing we can do that will stop it. What then? And how, amid all of this, can I possibly be feeling optimistic again? Have I completely lost it?

I’ve explored the long-term consequences of this conclusion before: in “Frontiers” (2009), and on The No Fear Pioneer. We’re left with a fundamentally difficult dilemma: What do we do when it’s time to go elsewhere and start the experiment over, but there is nowhere else to go on this Earth? Well, the only answer you come up with is damn near science fiction that doesn’t seem of much help to you, me, or even the next generation, even at the current, somewhat reinvigorated pace of our space ambitions. The obstacles to living, let alone thriving, elsewhere are huge and daunting — possibly far greater than our imaginations are capable of grasping. Success is a long way from today. But it’s coming. It’s our last and only resort. And while we therefore work toward its eventual fulfillment, we also have work to do here, striving for any short-term escape or mitigation of circumstances we can devise.

What I aim to do in this series is share everything I’ve managed to learn or figure out about The Way Out. I aim to help those who share my preferences to find their bearings and start on a course that will save them, that will save all of us.

I’ve titled this series “The Way Out” despite the realization that there is no single answer, but rather a myriad of possibilities. Each of us must ultimately chart his own course, based on his own unique circumstances and wishes. “The Way Out” is all of us, in aggregate, making long-term preparations for our kind to head toward the next place, and doing whatever can be done in the meantime to salvage this one. Each individual route is not contingent on the rest. We will each find our way through trial and error, by getting up every last time and using what we’ve learned to try again. When we find something that works, and that may work for others, we’ll share the benefit of our experience. Having a repeatable process for something is far more valuable than a few end results, and in this manner we may be able to cobble together something resembling one. The hope is that through this approach, we will all find our way to a better place. At the same time, however, you must know in your heart of hearts that your escape is also a uniquely personal matter, and cannot be allowed to be contingent on the success of any broader effort that may fail. It is sacrosanct, it will need to be the focus of your calmly determined efforts for quite some time, and, if you are anything like me, it is not negotiable. We will seek to ally our endeavors when we can. We will walk alone when we must.

Years ago, Bill Whittle (who I owe a tremendous debt of thanks that I will never be able to adequately repay, for all that he’s done through his superb work to save me from giving up in despair) floated the idea of “Ejectia” — an online community where people like us would be able to share our expertise and build a library of practical knowledge necessary to keep this free Civilization up and running. As fans of Bill’s writing, I and many other Eject! Eject! Eject! readers got very excited about the possibility, then disappointed when it became clear that building Ejectia was far more work than Bill and his volunteer elves could handle and wasn’t going to come to fruition, before I finally realized that it wasn’t necessary. What we wanted already exists in some form. It’s called The Internet. It’s social media. Opportunities to meet and connect across vast distances, and the aggregate knowledge of mankind available to anyone virtually for free, already out there and instantly accessible. And I suspect that Bill has reached much the same conclusion — because the future he articulated in “A New Beginning” does not hinge on any single effort. Rather, it is a matter of decentralized, voluntary initiative in diverse and numerous laboratories of innovation — yours, mine, and others.

Don’t get me wrong: There is value in specialized, shared-interest sites around which to network. BillWhittle.com and Ricochet.com, which I greatly enjoy despite finding almost no time to participate, come to mind. But let’s not forget to also leverage already-available general solutions. Twitter, for example, has been a huge boon in enabling me to meet and get to know others with kindred ideas, in ways that occasional blogging never managed to facilitate. We’re going to need to harness tools of this kind, to help us find our way.

I’ve argued against the idea that there is any single unique Way Out, but there is at least one unifying assertion that I do feel confident making: Running is not a strategy. A man who takes action purely in response to what he’s been forced to run from has only half a plan. An effective strategy must be active, not merely reactive. Playing defense alone isn’t going to cut it.

So if we’re not merely heading away from something, what are we moving toward? Bill outlined a glimmer of an idea in “A New Beginning” — the best idea I have yet seen. It is a concept in need of practical, implementable mechanics, but it offers a strong premise from which to proceed. Out-innovating our sclerotic, unsustainable, Industrial Age government institutions with highly adaptive, dynamic, decentralized, voluntary alternatives is the way to go. It’s the only way a free society has ever been able to thrive. Working out the possible mechanics of that, and pursuing other promising ideas, will be the subject of my ongoing posts in this series.

Another assertion I’m going to make is that culture leads, and is in many ways the nexus of our predicament. Bill has stated this many times in recent years, and I think he’s right. Of all that has troubled me, the growth of an out-of-control federal government, and the ever-growing taxes and mandates by which it struggles to sustain its insatiable appetites, are actually not even at the top of my list. The most onerous burden of all is the pervasive notion that we’re supposed to want what’s happening, that it should somehow be considered desirable progress. I cannot account for the myopia of others in embracing such a view, but I know complete absurdity when I see it. Plainly, none of this should be happening if we were on the course we are meant to be on. Thus, The Way Out is, as much as anything, a matter of one’s perspective and attitude. It is a state of mind. It’s about not letting your thoughts, ambitions, determination, or sense of your own bearings get dragged down by the insanity that may well happen to surround you.

I am setting forth a project for us — one to pursue systematically and methodically. The course ahead is a steady, undaunted one. We’re not about to stand still. We’re not just digging in and holding the line. We’re not merely running away from something either. We’re going places — places where others will fear to tread. So stroll down to your engine room and start checking on all systems. Your colleagues in this beautiful endeavor are going to need your contributions. They’re going to need to see your running lights on the horizon off their starboard bow. What you do matters. Running aground is not an option.

If you hear music in this, you’ve been gifted with something extraordinary: that diamond-hard remnant core that Bill has spoken of so eloquently. Whatever you do, don’t let that rare and precious spark go out. It’s everything that matters.

At the center of all this, even amid a worrisome fog of gloom, is what I see as a cheerful and practical, pragmatic approach. I have found that the gloom is at its worst when you’re focused down on the small picture, on reacting piecemeal to the daily inundation of “I can’t believe this is happening” stuff that you’re meant to be overwhelmed and incapacitated by. For all that blogs, Twitter, and the 24/7 news cycle have given me in terms of knowledge, they also excel at cultivating this toxic, bogged-down perspective. The big picture is much brighter than that, and hinges on irrepressible human potential and determination that our adversaries are incapable of suppressing with their petty narcissistic gloom. Our future is ours, and it’s wide open.

What’s in my heart is a combination of calm, methodical determination, and lightness at knowing and joyously and gratefully embracing what I have come to believe my is life’s greatest purpose. It is a gift to have to face this challenge, to get to be a part of the rebirth, the renaissance, of something new and beautiful and worthy of our exertions, however long it may take. We’re working toward building a place where the life of one’s own will again prevail unencumbered, and will have its due chance to thrive and be celebrated for the next long spell until, despite our best efforts, Civilization may again, perhaps inevitably, succumb to rust, and once more it will be time for those who choose to keep its foundational ideas alive to pack up and move on to the next frontier.

A Way Out is possible. I’m devoting my life to finding it and helping others to do the same. This, right here, is my declaration of intent.

I can’t promise answers, but I will do my best to log observations, explain my own path and discoveries, and link to useful insights and resources that I find.

Keep an eye on this series, and you’ll see the outline of my vapor trail. I’ll watch the skies for yours.

Godspeed, my friends. Take heart. Stay focused. The best is yet to come.