One nagging thought that’s troubled me for several years now has concerned the nature of “frontiers” — the character of those who strike out to populate them, what happens as the populace of a former frontier changes over time, and what to do when we run out of new frontiers to settle.

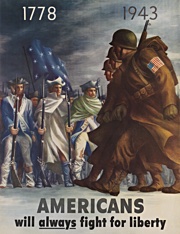

The United States began life as a frontier of far-flung colonies — colonies that came to be populated by people who were brave, bold, and/or desperate enough to give up every semblance of stability in their former lives and risk everything on the possibility of a new and, they hoped, better future on the other side of a formidable ocean — a future they knew full well they would have to fashion by their own exertions, at considerable risk, in a land of many unknowns.

Over the few centuries since, the US has become a new home to immigrants with similar circumstances, motivations, dreams, courage, and drive hailing from every reach of the planet. Many more who might have wished to begin new lives here, but were fearful of the risks this life entails, did not come, and in this way our melting-pot population became a self-selecting group largely characterized by a measure of boldness, guts, and — I dare say — genuine, honest-to-gosh audacity.

At the same time, of course, we’ve also set about increasing our ranks the old fashioned way. Those born here sometimes successfully absorb the spirit of the place, and grow up to share such courage, determination, independence, work ethic, and mettle as their immigrant ancestors bore. Others somehow don’t acquire these traits, and seeing as they’re already here, don’t have to get here, and typically stay, they end up edging our average bearings as a population a bit farther away from that rugged pioneer spirit.

Roughly speaking, then, relative rates of immigration and birth, coupled with our rate of success or failure at instilling a love of sweet Freedom in our newly minted Americans, combine to determine the vitality of the American Spirit. (I leave out emigration as a relatively insignificant contributing factor because — funny thing — that just doesn’t happen much here.)

This all leads me to a question that, to my scientifically-trained mind, is reminiscent of the grand cosmological question of whether we live in an “open” universe (one that will continue to expand without limit) or a “closed” universe (whose expansion will eventually be slowed and then reversed by mutual gravity, leading it to recollapse):

Does a frontier inevitably move?

Maybe the answer should be intuitively obvious. A frontier doesn’t stay a frontier forever. New places are discovered, and become the new frontiers, while the old, now-familiar places accumulate a sort of inertia and become stable.

Only, what happens when we run out of new places? What happens when the old, former frontiers become gradually less friendly to those who dare to dream the really big dreams, who aspire to wide-open unencumbered FREEDOM as far as the eye can see, but there’s nowhere else left for them to go?

Barring the discovery of an unforseen loophole in the laws of physics as we’ve thus far distilled them, we are prisoners of our own solar system, whose eight — er, strike that — seven other planets aren’t particularly hospitable to human habitation. At great cost and with enough of the hardy pioneer determination that birthed this nation it could be done, perhaps, but there is no other home remotely as cordial as this precious blue-green marble we inhabit within our grasp. Firefly fantasies aside, enterprising interplanetary homesteaders don’t have a whole lot of choices — or, really, any — right now.

This fact has been keenly on my mind as we watch our beloved United States of America become seemingly less and less recognizable to those of us who prize untrammeled individual freedom as the Founders did. As our population gradually loses that once-indomitable frontier spirit, and in the place of cherishing Sweet Liberty increasingly demands the safety, security, and closing of material equality gaps that are promised by a culture of regulation, entitlement, and coerced redistribution, so our dear country begins to seem less and less the kind of place for an intrepid frontiersman or frontierswoman to hitch their wagon to.

Perhaps the strangest thing of all about this “Europeanization” of America is the insistence on implementing such ideas here, despite the litany of nations in which they are already practiced (a fact it seems we’re incessantly reminded of by domestic critics of the classically American Way of life — you know, the ones who insist that Swedes, Venezuelans, and Cubans are somehow “freer than we are”). “Diversity” is not so much to be sought and celebrated, it seems, when it comes to socioeconomic policy — at least when doing so favors the continued existence of classically liberal (economically permissive rather than socially engineered) societies. Oddly, though the United States places no restrictions on emigration, proponents of Europeanization rarely seem to choose that route to obtaining the lifestyle they favor. There is something about this drive that seeks to transcend personal choice and impose that choice on others (ostensibly for their own good, of course).

Maybe the subduing of America is a “Holy Grail” of sorts for those who aspire to bring the benefits of benevolent statism to the whole world. Transnationalism has been a key aspect of Marxism from the get-go, and some ideas die hard. Today’s transnational progressivism, with its contempt for and active attempts to undermine international tax and regulatory competition, seems little different in this respect. Transnationalism seeks to seal off all avenues of escape for those who crave and seek greater economic freedom and commensurate responsibility for assuming risk. There would be no way out in a future world that agrees on and enforces the same set of laws, taxes and restrictions everywhere. The message from control-hungry transnationalists is clear: Tough luck, buddy. One Vorld Government vill be gut, und you vill like it.

If even the fiery, fiercely independent souls who inhabit the United States can be berated into giving up Liberty for safety, superficial equality, “fairness”, “niceness”, or just to be like everyone else, then there is truly no limit to statism’s ability to dominate a willing, submissive, or even just indifferent humankind. If we choose — on a personal, individual and not just national level — to continually seek the approval of others in an exceedingly self-conscious high-schoolish popularity contest, in the place of cherishing our right to scandalize the neighbors, then we are as good as done, and the American Idea is dead — much to the delight of its very vocal detractors.

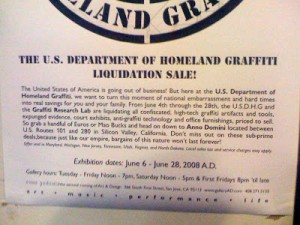

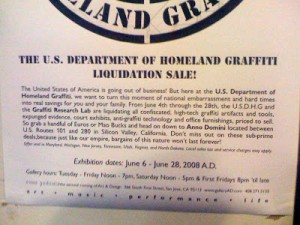

Take a good look at the following piece of contemporary art, which I took notice of among the 2008 “Zero1” exhibits in San Jose. Study it until you see the message behind the message.

In the final year of the Bush administration, this was shown as mockery and criticism of America’s conduct in waging the Global War on Terror, from the perspective of the sort of person who thinks we ought to be ashamed of ourselves rather than fiercely proud and doggedly committed to our nation’s defense in the wake of the 9/11 Jihadist attacks on US soil. The longer I studied this image, the more the eagle’s tear rang hollow. Is the artist’s intent really to express regret at the decline in opinions of America that he or she obviously feels is justified?

I think there’s a clear second meaning here, that’s picked up by those who go in for such stuff, and it is one of triumphant celebration. There are people — the artist included, I strongly suspect — who could not be more pleased by this development, who don’t merely feel ashamed of what they think we’ve become, but cannot stand even what we once were and have long stood for, and who cannot wait for the American Idea itself — the notion of your life on your terms — to fall in the world’s esteem, lose its luster and appeal, and fade away as an object of aspiration for millions upon millions the world over. They want mindshare for governing ideas of their own, and those ideas have little to do with freedom I’m afraid.

Friends, it’s no accident that the tongue-in-cheek “fire sale” that this exhibit advertised accepts “Euros or Mao Bucks”:

Why is it that we keep seeing these folks among the ranks of anti-war activists? It’s hard to avoid supposing that they are more accurately pro-war, but on the other side.

Look at the image again.

It is not a lament, but a victory banner. Those it speaks for feign disappointment, but in truth couldn’t be more pleased. America and what she represents falling in the world’s esteem. Mission Accomplished.

These fellow citizens and others like them aim to demoralize us with their moralizing — to tame, subdue, and crush the defiantly independent frontier spirit that makes us us — and I fear they may be succeeding.

How we got to this point from our ruggedly independent, defiantly freedom-loving, living-my-own-way who-cares-what-others-think frontier roots is a very long story. But the net change in our national character could hardly be more pronounced.

Living in the far-West former frontier “Gold Rush” state of California as I do, I feel acutely aware of the especially radical transformation my state has undergone since its settlement — crossing the full spectrum from initially wild and lawless open country to one of the most social-engineering-heavy and burdensomely taxed and regulated (or, if you prefer, most “progressive”) states in the Union. To some, this is desirable progress. To me, it is the slow, tragic dying of a cherished dream and ideal.

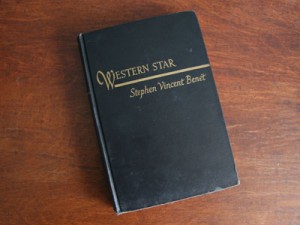

When I contemplate the Frontier, the “Invocation” of Stephen Vincent Benét’s epic poem “Western Star”, which I first mentioned a few years ago, always comes to mind. I’ve read this passage at home in far-West California; I’ve read it on vacation on a horse ranch in Wyoming, a state whose wide-open vistas preserve some of the last remaining fragments of the old frontier spirit. And it gives me a deep shiver. Every time.

Not for the great, not for the marvelous,

Not for the barren husbands of the gold;

Not for the arrowmakers of the soul,

Wasted with truth, the star-regarding wise;

Not even for the few

Who would not be the hunter nor the prey,

Who stood between the eater and the meat,

The wilderness saints, the guiltless, the absolved,

Born out of Time, the seekers of the balm

Where the green grass grows from the broken heart;

But for all these, the nameless, numberless

Seed of the field, the mortal wood and earth

Hewn for the clearing, trampled for the floor,

Uprooted and cast out upon the stone

From Jamestown to Benicia.

This is their song, this is their testament,

Carved to their likeness, speaking in their tongue

And branded with the iron of their star.

I say you shall remember them. I say

When the night has fallen on your loneliness

And the deep wood beyond the ruined wall

Seems to step forward swiftly with the dusk,

You shall remember them. You shall not see

Water or wheat or axe-mark on the tree

And not remember them.

You shall not win without remembering them,

For they won every shadow of the moon,

All the vast shadows, and you shall not lose

Without a dark remembrance of their loss

For they lost all and none remembered them.

Hear the wind

Blow through the buffalo-grass

Blow over wild-grape and brier.

This was frontier, and this,

And this, your house, was frontier.

There were footprints upon the hill

And men lie buried under,

Tamers of earth and rivers.

They died at the end of labor,

Forgotten is the name.

Now, in full summer, by the Eastern shore,

Between the seamark and the roads going West,

I call two oceans to remember them.

I fill the hollow darkness with their names.

Is it possible to read the above and not feel it in your bones?

All this has been on my mind for a seemingly very long time now, but it took this superb blog post by “VodkaPundit” Stephen Green to prompt me to finally compose my thoughts.

American freedom was a huge, sprawling, messy, brawling thing. It consumed everything and anything, and spewed out an unimaginable bounty. For some, the freedom was about growing their business and making money. For others, it was about growing their hair and making love. But it was always here, for anyone willing to risk the journey and leave behind the Old World and its old ways.

But now that we have this wonderful place, this precious idea — what are we doing with it?

Already, the government runs our children’s education and our parents’ retirement. Now we’re allowing it to usurp our banks and nationalize what remains of our auto industries. Within weeks, Washington promises a plan to dictate our health care. To do all this, we’ve let Washington run up enough red ink to impoverish our grandchildren. As if all that weren’t enough, the president still found the time to kick our friends in London and Tel Aviv while courting a genocidal, election-stealing maniac in Tehran. He even gave a speech in Cairo — that oppressed, impoverished Old World megalopolis — in which he assured the world that America really is no better than anywhere else.

Well, once upon a time, we were.

Absent a warp drive, a wormhole, or some other science fiction escape to an uninhabited Earth-like planet, it’s impossible to recreate the conditions which allowed the creation of these United States. It can’t be done; there aren’t any New Worlds left to discover. Our maps are all filled in.

If the Old World comes here, where does the New World have left to go?

When the Puritans were persecuted in England, they risked everything to come to America. When young Germans faced the Prussian army’s grip, they gave up their ancient towns to come here. When Jews faced the Czar’s pogroms, they gave up their bucolic steppes for the slums of New York. Rather than accept stagnant lives in their own countries, Latin Americans risked uncertain lives in America. Rather than accept far milder impositions than our own, America’s Founding Fathers risked their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor just to sign their names on parchment.

Anyone with nothing to lose and everything to gain — and bearing wits and character enough to risk it all — came here. They ventured here. To America.

Whatever liberty we have right here, right now, in America … well, for all practical purposes, that’s all that’s left anywhere. If France had our freedoms, there would be no French here. If China had it, there would be no Chinese here. If it existed in Latin America, there would be no Spanish spoken here. And so it goes.

And so if we, here in America, throw it all away in a fit of panic or pique, then what we once called “America” will become as false as a fairy tale.

By all means, read the whole, brilliantly worded thing.

One more thought in closing:

Remember the 2004 and 2008 presidential elections, when many on the left threatened to “seek asylum” in Canada if Bush or McCain won?

Those of us who cherish the classically American commitment to individual Freedom have no Canada. America is our last, best hope. Our opponents know it. And if we lose this ground for good, it seems to me we will have lost everything that matters.

For the sake of all we hold dear in this life, we mustn’t let that happen.

During a recent visit to Urban Ore, a sort of catch-all used junk/treasure store and minor Berkeley institution, I found myself sucked into the used book section. It’s inevitable, it seems — I do the same thing at antique stores, and have to keep a close eye on my watch when doing so, lest I lose all track of time browsing the worn spines with curious titles, leafing through pages of words once read and now mostly forgotten, as if searching for nothing in particular and something I can’t quite identify.

Among the more interesting relics I examined that day was a 1946 high school yearbook, whose first dozen or so pages were devoted to class-portraits-in-uniform of young men (and more than a few young women among them) who had served in the U.S. armed forces in World War II. I wish I could remember the moving words of humble gratitude that were placed therein to honor their service (and in many cases their ultimate sacrifice). I wondered if the yearbook committees of today were addressing comparable subject matter with such reverence.

The yearbook went back on the shelf, but another book that caught my eye went home with me — a somewhat yellowed and tattered but otherwise intact copy of a poem by Stephen Vincent Benét, whose earlier work “Listen to the People” I had read and deeply enjoyed. “Western Star” is the title of this one, a book-length story, published in 1943, about the American frontier and those who made and lived it.

I picked it up and started reading tonight, and am enjoying it very much so far. Three pages into the “Prelude” came a passage that seemed especially appropriate to excerpt here:

The stranger finds them easy to explain

(Americans, I said Americans,)

And tells them so in public and at length.

(It’s an old Roman virtue to be frank,

A tattered Grecian parchment on the shelves,

Explaining the barbarians to themselves,

A lost, Egyptian prank.)

Here is the weakness. On the other hand,

Here is what really might be called the strength.

And then he makes a list.

Sometimes he thumps the table with his fist.

Sometimes, he’s very bland.

O few, stiff-collared and unhappy men

Wilting in silence, to the cultured boom

Of the trained voice in the perspiring room!

O books, O endless, minatory books!

(Explaining the barbarians to themselves)

He came and went. He liked our women’s looks.

Ate lunch and said the skyscrapers were high,

And then, in state, passed by,

To the next lecture, to the desolate tryst.

Sometimes to waken, in the narrow berth

When the green curtains swayed like giant leaves

In the dry, prairie-gust,

Wake, with an aching head, and taste the dust,

The floury wheat-dust, smelling of the sheaves,

And wonder, for a second of dismay,

If there was something that one might have missed,

Between the chicken salad and the train,

Between the ladies’ luncheon and the station,

Something that might explain one’s explanation